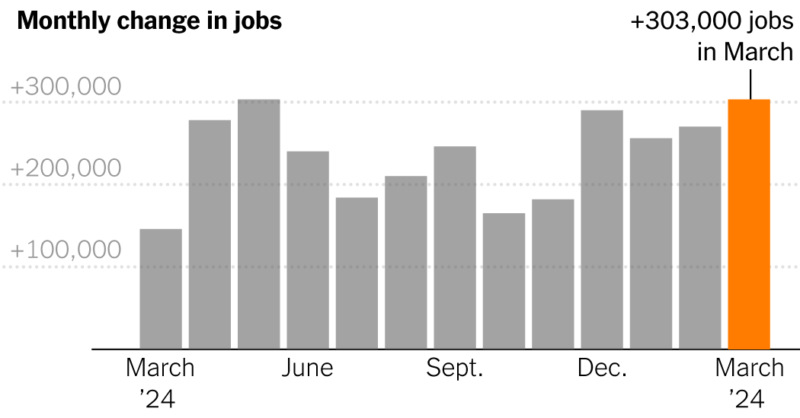

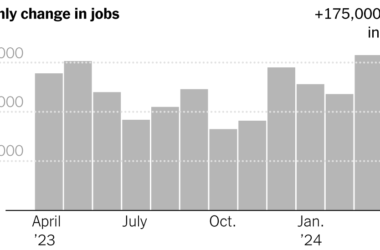

Another month, another burst of better-than-expected job gains.

Employers added 303,000 jobs in March on a seasonally adjusted basis, the Labor Department reported on Friday, and the unemployment rate fell to 3.8 percent, from 3.9 percent in February. Expectations of a recession among experts, once widespread, are now increasingly rare.

It was the 39th straight month of job growth. And employment levels are now more than three million greater than forecast by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office just before the pandemic shock.

The resilient data generally increased confidence among economists and market investors that the U.S. economy has reached a healthy equilibrium in which a steady roll of commercial activity, growing employment and rising wages can coexist, despite the high interest rate levels of the last two years.

From late 2021 to early 2023, inflation was outstripping wage gains, but that also now appears to have firmly shifted, even as wage increases decelerate from their roaring rates of growth in 2022. Average hourly earnings for workers rose 0.3 percent in March from the previous month and were up 4.1 percent from March 2023.

“The vanishingly few areas to criticize this labor market are melting away,” said Andrew Flowers, the chief labor economist at Appcast, a recruitment advertising firm.

Some have worried that as the booming labor market recovery gave way to a milder expansion, job growth would mostly narrow to less cyclical sectors like government hiring and health care. Gains in health care — including hospitals, nursing and residential care facilities and outpatient services — led the way in this report. But job growth, for now, remains broad-based.

The private sector added 232,000 jobs overall. Construction added 39,000 jobs in March, about twice its average monthly gain in the past year. Employment in hospitality and leisure, which plunged during the pandemic, continues to bounce back and is now above its February 2020 levels.

The “continued vigor,” said Joe Davis, the global chief economist at Vanguard, has come from “household balance sheets bolstered by pandemic-related fiscal policy and a virtuous cycle where job growth, wages and consumption fuel one another.”

President Biden declared the report a “milestone,” noting that the economy has created 15 million jobs since he took office and began a set of programs meant to boost growth. “We’ve come a long way, but I won’t stop fighting for hard-working families,” he said in a statement.

Data analysts note that better-than-expected gains in business productivity and work force participation have added fuel, too. Recent data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis shows corporate profits at a record high.

Officials at the Fed, which rapidly raised interest rates in 2022 and early 2023 to combat inflation, have expressed cautious optimism that they are approaching their goals of low unemployment and more stable prices.

Inflation has fallen drastically from its peak of 7.1 percent, according to the Fed’s preferred measure. But it ticked up in February to 2.5 percent, still a half-percentage point away from the Fed’s target. And some worry that rising oil prices or geopolitical chaos could upend the delicate state of affairs.

Reasons for caution go beyond global events.

Guy Berger, director of economic research at the Burning Glass Institute, which studies the labor market, noted that though layoff rates are near record lows, other data on hiring was “consistent with an unemployment rate just under 5 percent” based on past business cycles.

And some labor economists believe that elevated borrowing costs for consumers and businesses, which were steered higher by the Fed, are poised to crack certain parts of the economy the longer businesses have to live with them.

Nancy Vanden Houten, lead U.S. economist at the advisory firm Oxford Economics, said that the strong job growth need not deter the Fed from lowering interest rates — something it is projected to do three times this year — and adding a layer of insurance to the ongoing business expansion.

“The Fed does not need to see a weak labor market to begin cutting rates but will be guided by readings on wage growth and inflation, which we expect to show more progress toward the central bank’s objectives in the next few months,” she wrote in a research note.

Even as narratives about the U.S. economy among top experts have waffled between jubilant relief and stubborn concern that the best of this business cycle was finished, in the aggregate the labor market has consistently been vibrant since 2022; almost uneventfully so.

But the underlying details do provide insights into potential shifts that may affect the mix of hiring and commercial activity going forward.

Employment growth in sectors like professional and business services, finance and information remains soft. Daniel Zhao, the lead economist at the career site Glassdoor, pointed out that these three sectors collectively added just 10,000 jobs in March — a fresh indication of how white-collar employers have grown much more picky since their hiring spree during the pandemic.

“Companies are hiring selectively, prioritizing quality over quantity,” said Tom Gimbel, the chief executive of the LaSalle Network, a Chicago-based staffing and recruiting firm.

The upside is that those workers are the most likely to be high earners in the first place; homeowners with low-cost, fixed-rate mortgages shielding them from rental inflation, and investors whose portfolios have been on an eye-popping bull run since fall.

Lower-wage earners, for their part, are experiencing a job market less hot than a couple of years ago, when switching jobs in search of better pay and benefits frequently garnered double-digit percent raises. The market is, however, still providing opportunities for earnings growth not seen since the late 1990s, according to key Fed measures.

In an interview with Bloomberg in March, Liz Everett Krisberg, the head of the Bank of America Institute, noted a crucial overarching reality for households: The monthly median value of savings and checking balances is more than 40 percent higher than in 2019 for all income levels tracked by the bank.

Delinquencies are on the rise for subprime borrowers of cars and credit cards. But the overall percentage of household disposable income going to debt payments is still below its prepandemic low.

Mark Zandi, the chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, has been among the more bullish financial commentators since recession concerns grew in 2022.

But a year ago, when the regional banking system began to tremble a bit from interest rate shocks, he grew more worried. Mr. Zandi advised his son, an entrepreneur, that he was unlikely to get a line of credit because bank lending was probably about to tighten.

“He knocked on JPMorgan Chase’s door and they gave him a line of credit within two hours,” Mr. Zandi said with a laugh. “And, you know, it was a pretty sizable line.”

That turn of events is emblematic of a little-noticed shift in business conditions. Since the middle of last year, when economic growth greatly exceeded forecasts, the share of banks tightening lending to small businesses has eased substantially. That trend is in line with an emerging conviction among business leaders that a downturn is not imminent, and a potentially elongated expansion makes betting on upstart firms more attractive.

Frustration with the cumulative rise in prices over the last three years continues to agitate consumer sentiment. But consumers and businesses, in many ways, are still in healthy shape overall, said Daniel Alpert, a senior fellow in financial macroeconomics at Cornell Law School and a founding managing partner of Westwood Capital, an investment bank.

“Were it not for the post-pandemic inflation spike and high interest rates,” he said, this economy “would be hailed as one of the greatest turnarounds in history.”