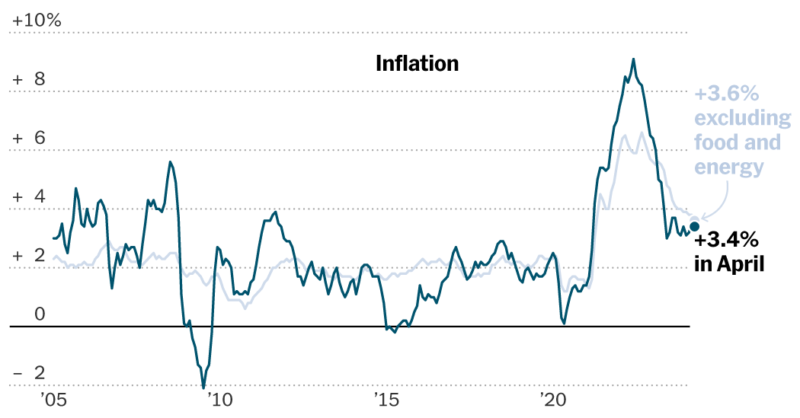

Finally, some good news on inflation.

The Consumer Price Index climbed 3.4 percent in April, down from 3.5 percent in March, the Labor Department said on Wednesday. The “core” index — which strips out volatile food and fuel prices in order to give a sense of the underlying trend — rose 3.6 percent last month, down from 3.8 percent a month earlier. It was the lowest annual increase in core inflation since early 2021.

The report followed three straight months of uncomfortably rapid price increases that rattled investors and worried policymakers at the Federal Reserve. Economists cautioned that one month of encouraging data was far from enough to put those worries to rest. But they said that the data should ease concerns, at least for now, that inflation is re-accelerating.

“I would characterize it as a small step in the right direction,” said Stephen Stanley, the chief U.S. economist at Santander.

Both overall and core prices rose 0.3 percent from the previous month, down from 0.4 percent in February and March.

Inflation fell rapidly last year, giving rise to hopes that the Fed was on the verge of succeeding in its effort to rein in price increases without causing a recession, and that the central bank could soon begin to cut interest rates, which are currently set at about 5.3 percent. But progress stalled in the first three months of the year, and investors have all but given up hope of rate cuts before September.

The inflation report on Wednesday is unlikely to change those expectations on its own. But it could be a step toward giving policymakers confidence that inflation is returning to normal, which they have said they need before they begin to cut rates. And it is likely to further reduce the chances — already remote — that policymakers could decide to raise rates rather than cut them.

“I think there will be something of a sigh of relief from the Fed, but at the same time there’s still work to be done,” said Sarah House, a senior economist at Wells Fargo.

Investors cheered the news. The S&P 500 index was up about 0.7 percent at 11 a.m. The yield on the two-year Treasury note, which is sensitive to changes in interest rate expectations, fell sharply after the numbers were released, as investors appeared to have dialed back how long they expected interest rates to stay elevated.

The report was also a welcome break for the White House from a string of bad inflation data that has helped inflame voter discontent over President Biden’s handling of the economy.

“I know many families are struggling, and that even though we’ve made progress we have a lot more to do,” Mr. Biden said in a statement released by the White House. He called bringing down inflation his “top economic priority.”

Wednesday’s data showed notable progress on several fronts. New and used car prices and airline fares fell outright in April. So, crucially, did the price of groceries, long one of the most painful categories for consumers. Even housing, the largest component of the inflation index and one of the most stubborn, showed cautious hints of improvement.

Gasoline prices, on the other hand, rose a seasonally adjusted 2.8 percent in April from March. Car insurance rates also continued to surge, albeit more slowly than in the month before. And services prices more generally continued to rise at a faster clip than policymakers were likely to consider acceptable.

Still, while Wednesday’s report contained some mixed signals, it did at least stop the bleeding after several months of troubling news.

Had the data come in hotter than anticipated yet again, it could have led policymakers to conclude that high rates need even more time than investors currently expect to bring inflation to heel. Speaking at an event in Amsterdam on Tuesday, Jerome H. Powell, the Fed chair, reiterated that recent inflation readings had made him more cautious about cutting rates.

“We did not expect this to be a smooth road, but these were higher than I think anybody expected,” he said. “What that has told us is that we will need to be patient and let restrictive policy do its work.”

Any further delay would add to the pain for low- and moderate-income Americans, who are increasingly struggling to manage the burden of higher borrowing costs. On Tuesday, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York released data showing that a rising share of borrowers are falling behind on their credit card bills as rates on those debts have skyrocketed. And data from the Commerce Department on Wednesday showed that retail sales were flat in April, a possible sign of caution among inflation-weary consumers.

The inflation data on Wednesday contained hints of improvement in one of the most important and troublesome categories of inflation: housing. Rents were up 5.4 percent in April from a year earlier, the smallest annual gain in nearly two years.

But progress on housing costs remains uncomfortably slow. For more than a year, forecasters have been predicting that the government’s measure of housing inflation would ease, citing private-sector data showing rent increases slowing.

Instead, housing costs in the Consumer Price Index have continued to rise more quickly than before the coronavirus pandemic, a pattern that continued in April. And recently, some private-sector measures have begun to show rents rising faster again as well.

“The narrative on rents was that they were going to continue to soften as 2024 played out,” said Rick Palacios Jr., the director of research for John Burns Research and Consulting, a real estate data firm. “We don’t see that. If anything, we see it picking up.”

Housing is by far the largest monthly expense for most families, which means that it also plays an outsize role in inflation calculations. If rents keep rising at their current rate, it will be hard for inflation overall to return to normal.

Still, taken as a whole, the April data could restore some confidence that policymakers will be able to keep bringing down inflation without causing a recession. The Fed appeared on track to do that last year, defying predictions that high interest rates would inevitably cause a large increase in unemployment.

But as the fight has dragged on, some economists have begun to question that narrative. Job growth slowed more than expected in April, and the unemployment rate has gradually crept up.

“The labor market has held up so well,” Ms. House said. “But the longer we keep interest rates where they are, the more I get worried about the labor market side.”

Jeanna Smialek, Jim Tankersley and Joe Rennison contributed reporting.